Etosha National Park is Namibia’s premier wildlife reserve, covering about 8,600 square miles in northern Namibia.

This park is easily navigable by self-drive.

Unlike many parks in East Africa or neighboring Botswana, it’s almost impossible to get lost in Etosha, as there is a limited network of well-maintained roads, and vehicles are not allowed to travel off of them.

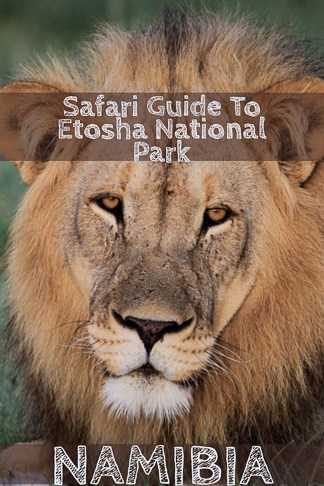

Etosha is not quite a Big 5 game park as the Cape buffalo does not make a home here.

However, the other four — elephant, rhino, lion and leopard — do reside along with many other stunning and iconic species of African wildlife.

“Big 5” doesn’t refer to the best or most popular animals to see, rather it was coined by early European hunters to refer to the five animals most dangerous when they are injured.

A drive through Etosha National Park offers perhaps the best chance of anywhere on the planet to see a Black Rhino in its natural habitat.

Etosha National Park is home to nearly a third of the entire global Black Rhino population.

Black rhinos differ from white rhinos primarily in their feeding behaviour which corresponds to a difference in the structure of their mouths.

White rhinos have a wide, flat upper lip to graze at ground level.

(Although they live in Etosha also, Hluhluwe-iMfolozi National Park in neighbouring South Africa is one of the best places to spot white rhinos.)

Black rhinos have a long, hook-like upper lip that can wrap around branches of bushes to strip off the leaves.

Namibia’s black rhinos have adapted to tolerate extremely dry desert conditions and can survive for several days without water.

In June, which is near the front end of the dry season, I saw this dainty baby rhino at a waterhole near sunrise.

Sunrise and sunset bestow the most magical lighting on the wildlife, often a golden or pink colour.

As on any safari, no animal sighting is guaranteed.

The best chances, though, come during the dry season when animals congregate around waterholes on the open grasslands, where it is easy to see large numbers of animals as well as more rare ones that keep to the woodlands when they can.

This is generally recognized as May through November.

Unlike many other wildlife parks, Etosha doesn’t have a river within its borders.

Without a natural ribbon of water running through the park, the animals are particularly drawn to the waterholes — many of which are formed by natural springs.

In contrast, others are man-made, filled by boreholes for the benefit of tourist viewing.

The colours of the dry season are wonderful — golden grasses and chalky blue sky (though the latter is the result of farmers burning their fields after harvest).

The wildlife stands out easily against the drying ground cover, which also gets sparser and lower as the dry season progresses and the herbivores eat what is available.

I love when multiple species of animals hang out together, such as the oryx (also called gemsbok), blue wildebeest and springbok below.

I think it could safely be said you’re guaranteed to see plenty of animals in the dry season, but if you have a particular animal in mind you want to see, the longer you stay, the better the odds.

My recommendation is to book a bare minimum of 3 full days in the park to increase your odds.

Want More information about Etosha National Park.

In the wet season, January through March, this could mean a lot of driving without a sighting, so perhaps you need a little more dedication and optimism.

Still, it also means cheaper accommodations by about $1000 NAD (roughly $60 USD) per night, and often have the roads and animals all to yourself.

And you may be surprised by some amazing sightings in the off-season. I was warned I was unlikely to see much then, but in March I saw elephants, plenty of antelope species and three male lions super close-up.

The park was established around the enormous Etosha Salt Pan, Africa’s largest salt pan. It was once a freshwater lake until its primary tributary river changed course and the lake slowly dried up.

Smaller contributing rivers now mostly soak into the ground before they reach the salt pan.

It’s a barren, forbidding place in the dry season, but full of colour in the wet season.

A particular joy in this time of year is watching the rain clouds gather across the pan and release showers that form temporary pools and bring the pan to life.

Any time of year, birds abound throughout Etosha National Park.

Even if the large mammals are more difficult to spot in the wet season, birds will still undoubtedly entertain a visitor — from social weavers to lone eagles, dazzling colours to clever camouflage, the largest ostrich to the smallest tit, Africa will turn just about anyone into a birder!

The lilac-breasted roller is particularly popular with tourists, including me! It’s a sheer delight to spot this little gem of nature.

The tourist roads and camps primarily skirt the southern and eastern edges of the pan.

A series of loop roads branch off the main road. A park map is very easy to follow.

The densest concentration of waterholes and loop roads is the southern stretch between Anderson Gate and Von Lindequist Gate.

Conveniently, there is a rest camp near each gate.

Near the Anderson Gate, an overnight at Okaukuejo Camp is highly recommended.

It’s probably the most popular camp inside the park, and for a good reason.

Situated at a busy waterhole, there are plenty of benches, including a small grandstand, to sit on to watch the wildlife.

When I was there in March (the wet season), animal visitations were extremely sparse.

When I was there in June, the dry season, it was a veritable wildlife city … so many different creatures, many of them interacting with one another.

At night, floodlights shine on the waterhole, as many animals visit after the sun goes down.

The lights do not seem to bother the wildlife, and it makes for an exciting viewing experience.

While bush camps in African wildlife parks are their own form of excitement, you can’t usually hang out outside at night to see what wildlife comes around — you’re generally sequestered in your tent.

One night at the Okaukuejo waterhole I watched a showdown between a black rhino and an elephant.

Although the rhino was the smaller of the two, he had no tolerance for the elephant and kept pestering him to move.

Finally, the elephant filled his trunk with water and blew it at the rhino. Point goes to the elephant!

The basic chalets are simple but nice and clean.

My friends rented a premier chalet, however, and it’s quite swanky with two floors and a perfect view of the waterhole from the second-story balcony.

Namutoni Camp, originally a German fort built around the turn of the 20th century and later becoming a South African army base, is near the Von Lindequist Gate.

One friend of mine’s father was an officer at the fort in the 1970s and 80s during the South African Border War, and another friend of mine was a conscripted soldier there.

For a foreign visitor, the fort seems like a piece of history, but it is still breathing memories for many Namibians.

The Border War didn’t conclude until 1990 when Namibia finally gained its independence from South Africa.

Namutoni also has a waterhole with viewing benches and a floodlight at night. You can have drinks atop the fort walls — the perfect spot for a sundowner with a far view of the landscape as you watch the iconic African sun lower herself below the horizon.

North of Von Lindequist Gate is a less-visited part of the park where you can stay at the absolutely lovely Onkoshi Camp, whose chalets are on stilts right at the edge of the Etosha Salt Pan.

Here, animals graze directly below you.

I only saw various antelope species while I was there, but a Namibian friend of mine says he often has elephants coming right up to his chalet.

He typically rents the Honeymoon Chalet. You can watch all the animals, the fabulous African sunsets and the legions of stars rotate around the night sky outside on your private balcony or from inside lounging on your bed that faces the pan.

Onkoshi is a “low-impact” camp and runs primarily on solar power. Its swimming pool is delightfully situated to look out over the vast expanse of the pan.

There are no self-drive game viewing loops near Onkoshi, so game drives are booked through the lodge.

This offers a refreshing and serene opportunity to enjoy the wildlife and scenery without masses of other tourists and their vehicles.

Some camps, such as Namutoni, have campgrounds as well as chalets.

Olifantsrus Camp, in a more remote part of western Etosha, has only campsites but is worth a stop if you’re in the area, even if you aren’t camping, to check out the excellent hide.

The camp is named for the propensity of elephants (Olifants) to stop by. In my brief visit, I only saw a herd of red hartebeest, but they aren’t a particularly common animal to see.

Although I never saw the notoriously elusive leopard in Etosha, I did see my favourite African animal — the cheetah!

Although the three brothers I saw were partially hidden in tall grass, just finishing off a meal, chances are generally good of spotting cheetahs in the park.

Etosha National Park offers first-time safari-goers and well-travelled safari aficionados equal enjoyment.

Each month of the year offers its own particular charm, whether it be in the wet season or the dry.

The accommodations inside the park — six in total — provide the perfect launch pads for game drives.

Etosha National Park is definitely one of the best national parks in Africa to see wildlife.

And because most areas are accessible by self-drive, eliminating the need to hire a guide, it lends itself to a more affordable safari than is available in a lot of other African national parks.

Author bio: Shara Johnson plots her travels abroad from her picturesque home in the Rocky Mountains of Colorado.

Although she writes primarily literary creative nonfiction, her narrative travel blog helps her remember in greater detail, her amazing travels to seven continents.

Annie Berger

Sunday 6th of December 2020

What a stunning introduction to Etosha National Park - thank you!